Police Accountability in Chicago: from Data Dump to Usable Data

Obtaining raw data is great—but having analyzable data is what makes it possible to build legal cases and hold bad actors accountable. Fortunately, activists and investigators are succeeding at getting their hands on raw data, through lawsuits and Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. But it’s complicated: a massive “data dump” may not be analyzable as is, and can overwhelm the recipient with evidence that’s trapped in an adversarial format. A windfall of data may come in the form of written reports or letters,  which are unstructured data, and require thousands of person-hours to be processed into structured data, such as a spreadsheet, that lend itself to analysis.

which are unstructured data, and require thousands of person-hours to be processed into structured data, such as a spreadsheet, that lend itself to analysis.

The Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG) has been turning raw data into analyzable data for nearly 30 years—but processing data is only one piece of HRDAG’s “radical service” model. Typically, HRDAG spends hundreds of hours training partners, teaching them how to train their partners, building tools to help with their work, and empowering them to take the lead in their communities.

A lot of crimes never get reported, except for informally in communities where people tell each other. If we can generate useful records of what does get reported, that’s one way of honoring the limb that someone walked out on to report a crime.

— Tarak Shah, HRDAG data scientist

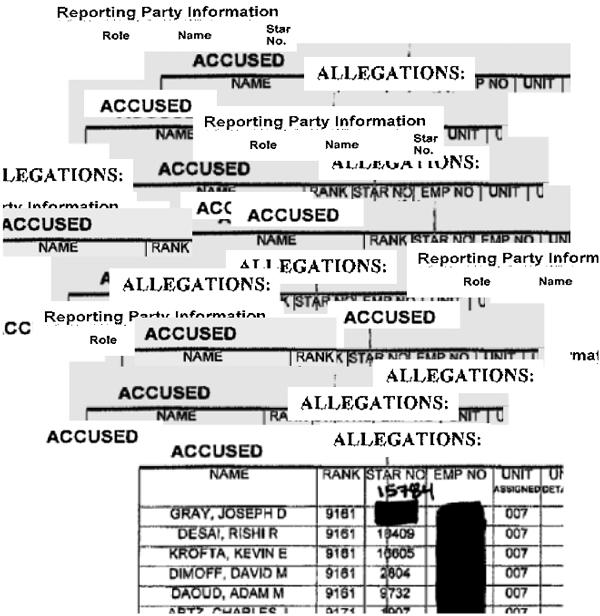

In 2014 and again in 2020, a Chicago grassroots organization, the Invisible Institute, won lawsuits that granted them access to decades of complaints of misconduct by Chicago police officers. Hundreds of thousands of complaints were suddenly made available in a variety of formats, from written summaries of allegations (unstructured data) to tables listing names, rank, dates, offense, and more (structured data). The Institute made scanned images of the documents available online, via the Citizens Police Data Project, and users can search for complaints using dozens of filters such as police beat, type of offense, demographics, or police officers’ names. But to further harness the data for large-scale accountability projects, they must be structured.

HRDAG stepped in to help the Institute bridge the gap between raw data and analyzable data. In the summer of 2019, HRDAG hosted Trina Reynolds-Tyler as their human rights intern, training her how to organize large-scale datasets. Trina is now the director of data at the Invisible Institute.

Over the past couple of years, HRDAG team members Tarak Shah, data scientist, and Patrick Ball, director of research, have continued to work closely with Trina and the Institute to process their windfall of police records. In part, they do this by meeting weekly with Trina to train a Chicago-based team of analysts and volunteers, continually honing a process to mine the data and code, or tag, each record in ways that will structure the data and make it usable for any number of future investigations. The goal is to make the records easy to find and identify for investigations that might explore, for example, officers targeting people based on their perceived sexual identity or disability status. Importantly, the coders are tagging records with all the violations described in the report, which enables a single record to serve as evidence in different types of investigations. This is a departure from how the police department administration currently handles the complaints, which is to categorize each complaint into a single category, usually the “most serious” offense, which essentially buries the other allegations described in the report.

Tarak, Patrick and HRDAG consultant Michelle Dukich meet regularly—several times a week—with Institute team members to design a strategy that will help the team use optical character recognition to extract narratives from scanned documents and machine learning to tag them. The result is structured datasets, with relevant sentences extracted and placed in the correct row or column. Even better, these newly structured data become training data that can be used to further teach machine-learning tools how to process the records.

Another project that Tarak is working on with the Institute is Beneath the Surface, which looks specifically for allegations of gender-based violence and tags the records accordingly. Often, when complainants report sexual misconduct or violence by police, the allegation gets buried through official coding procedures. For example, an incident where a police officer took a woman into a bathroom, forced her to remove her clothes, and then groped her, is coded as an “improper search of person.” Beneath the Surface will raise the visibility of this under-documented form of misconduct, which will raise the visibility of its survivors, who are often Black women or gender nonconforming people.

“We believe the gender-based violence we’re documenting is made invisible or under-documented,” says Tarak. “In the last decade we’ve seen new attention to police violence, specifically shootings in public of Black cis men. That’s a very serious thing. We want to make sure that’s not the only police violence that becomes visible.”

While the troves of raw data in Chicago can help us answer questions about which armed agents of the state were doing what to whom, it’s important to remember that the records we gain access to represent only a subset of incidences of police violence. In Chicago, the documents we have access to are thanks to those citizens brave enough to report their encounters with police. We must assume there are many, more incidences of violence and misconduct. The incidents we know about represent only a fraction of actual incidents of misconduct.

“A lot of crimes never get reported, except for informally in communities where people tell each other,” says Tarak. “If we can generate useful records of what does get reported, that’s one way of honoring the limb that someone walked out on to report a crime.”

There are ongoing debates about the role of armed agents of the state and whether they actually maintain public safety. Up to half of a city’s budget might go to supporting the police department, because they have convinced us that the world is dangerous and they keep us safe.

“But many crimes are neglected and do not get investigated, leading to things like backlogs of untested rape kits, not to mention the invisibility of crimes committed by the agents of the state themselves” says Tarak, “so it’s not clear who’s made safe.”

These institutions find themselves too easily acting with impunity. It’s the mission of organizations like the Invisible Institute and HRDAG to help affected communities and their allies discover how to collect, preserve, and analyze data to hold these institutions accountable and challenge impunity. One important step is teaching communities how to get the most out of the data they find themselves holding.

Image: David Peters.

HRDAG partner stories:

Quantifying Police Misconduct in Louisiana

Scraping for Pattern: Protecting Immigrant Rights in Washington State

Police Violence in Puerto Rico: Flooded with Data

Building Capacity In Colombia: Truth And Reconciliation

Police Accountability In Chicago: From Data Dump To Usable Data

Protecting the Privacy of Whistle-Blowers: The Staten Island Files