Scraping for Pattern: Protecting Immigrant Rights in Washington State

With projects focused on protecting immigrant rights, the University of Washington Center for Human Rights (UWCHR) realized it needed a better understanding of the detention and deportation pipeline. That pipeline—the process that identifies non-citizens for arrest and eventual deportation—seemed to be changing, for the worse, during the Trump Administration, but it was unclear exactly how. The UWCHR wanted to answer this question: “What is happening across the state of Washington?”

To that end, project coordinator Phil Neff and the Center undertook research initiatives—the Immigrant Rights Observatory and Human Rights at Home—to learn more about how immigration laws were being enforced and what the patterns of apprehension were. And this is how the UWCHR ended up with more than 4,000 pages of forms known as I-213s.

To that end, project coordinator Phil Neff and the Center undertook research initiatives—the Immigrant Rights Observatory and Human Rights at Home—to learn more about how immigration laws were being enforced and what the patterns of apprehension were. And this is how the UWCHR ended up with more than 4,000 pages of forms known as I-213s.

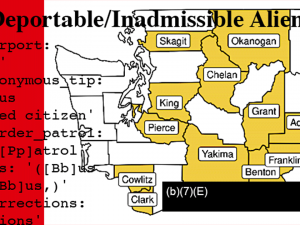

An I-213, or “Record of Deportable/Inadmissible Alien,” is a form generated whenever someone is apprehended by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and it can supply quantitative and qualitative information that’s more specific—and useful—than the aggregated data supplied by ICE and CBP.

“Dozens of people, including outside partners, have interacted with the data resulting from the I-213 scraping. Our team has used this data to check compliance [with the 2019 and 2020 laws].” —Phil Neff, UWCHR

“There’s still a lot of opacity in how ICE silos off their information, and the aggregated data don’t report on the exact location of the apprehension,” says Neff. “But the I-213s include a narrative of the apprehension, with fine-grained detail.”

One of the biggest links in the detention and deportation pipeline is the local police and jails. According to a state law passed in 2019, known as Keep Washington Working, and another in 2020, the Courts Open to All Act, local police, sheriff’s deputies, and jail officials are not allowed to give tips to ICE or CBP for making civil immigration arrests. But these laws are enforced with a wide range of consistency, and in some counties the local forces were continuing to collaborate with federal agents for immigration enforcement. Some jails continued to request “place of birth” information, despite the prohibition, continued to share it with ICE and CBP agents, and even placed “immigration holds” on detainees to facilitate their arrest by the federal agents.

In 2018, after the Department of Homeland Security refused to honor the UWCHR’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests for the forms, the Center sued, and won access to the forms created by ICE and CBP. Over the course of about a year, May 2020 to June 2021, ICE released 10 installments of I-213s to the Center, comprising more than 4,000 pages. Each form has about 50 data fields and the multi-page narrative mentioned earlier.

“In the past, when we got less information, we’d hand it off to a student who would make a spreadsheet,” says Neff. “But when we got these, we needed a procedure to pull data from the forms. We never could have done it without Tarak and Maria.”

Tarak Shah is a data scientist at Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG), and he and statistician Maria Gargiulo created a data processing pipeline that was able to handle the potentially overwhelming volume of files. They wrote the logic for processing the data, organizing the data, scraping all the text, slotting it into its respective fields in a data structure, and more.

“Then we were able to start counting things,” says Neff. “What Tarak did is written in such a way that it’s clear and easy to extend. Initially we were interested in 12 key text fields and ignored the rest, but over time it’s been relatively easy for me to add in more fields because I have a model for how to do this.”

Neff and his team have been able to analyze the scraped text and search for key words such as “jail” in order to gain insight into where immigration arrests are being made. “Dozens of people, including outside partners, have interacted with the data resulting from the I-213 scraping. Our team has used this data to check compliance [with the 2019 and 2020 laws].”

Neff has collaborated with HRDAG before, when he was involved in Unfinished Sentences, the Center’s project supporting survivors of war crimes in El Salvador, and analysis of The Yellow Book, a secret document created by Salvadoran military intelligence during the 1980s, containing the names and photographs of nearly 2,000 Salvadorans considered “delinquent terrorists,” including not only leaders of the FMLN guerrillas, but also human rights advocates, labor activists, and civilian political figures. “For this immigration rights project, we used the same methodology that we used around war crimes in El Salvador,” he says.

In 2020, the Center released their first report about the implementation and compliance of the 2019 law, focusing on county sheriffs and jails. Naturally, it was of interest to the state legislators who championed the law, and to the Center’s local partners on the front lines of immigrant rights advocacy in Washington state, as well. The report received mixed reactions from jurisdictions that were called out for violations. The project’s partners corresponded with jurisdictions identified as having problematic practices, with a range of responses. Some jurisdictions were less responsive, insisting that they were only sharing information that is, in fact, already public, so it’s not a violation. But then, there were heartening responses from other local officials who said they would comply with the law.

The I-213 project is ongoing, and Neff and the UWCHR now have enhanced capacity to carry it out without the further help of HRDAG. “What has been most useful to our Center and grown our capacity has been the ongoing mentorship that I personally have received from folks at HRDAG around principled data processing and coding, and just having a structure in place through which to carry out data related projects,” says Neff.

HRDAG partner stories:

Quantifying Police Misconduct in Louisiana

Scraping for Pattern: Protecting Immigrant Rights in Washington State

Police Violence in Puerto Rico: Flooded with Data

Building Capacity In Colombia: Truth And Reconciliation

Police Accountability In Chicago: From Data Dump To Usable Data

Protecting the Privacy of Whistle-Blowers: The Staten Island Files

Image: David Peters, 2022.