All of the ways we remember: How data scientists hold memory with and for survivors

Structural Zero Issue 07

I.

Earlier this year, I attended a convening of organizers working on police demilitarization, organized by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) and held at the Ben Lomond Quaker Center in Santa Cruz County, nestled in an old growth redwood forest.

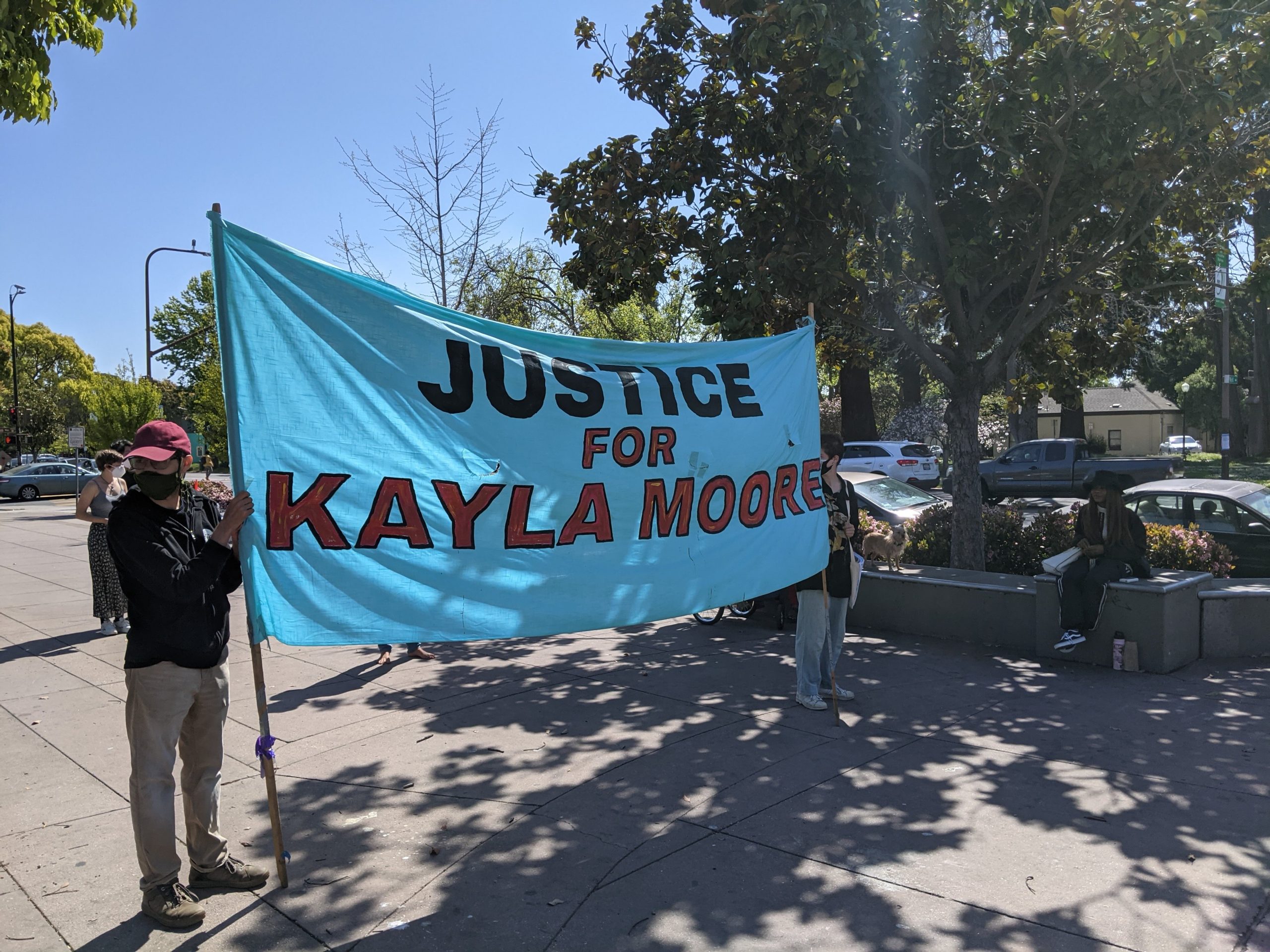

The convening brought together organizers from around California working on AB-481 and demilitarization. Among the attendees were a number of members of the Love Not Blood Campaign, an organization of survivors of police killings, people who decided to turn their grief and anger into action. These families have played a key role in a number of recent legislative changes and reforms in California, including the passage of SB-1421 and SB-16, which in turn have made my work possible.

Senator Nancy Skinner, who authored the bills, has spoken about the killing of Oscar Grant in Oakland a decade before the passage of SB-1421. Oscar’s family were her constituents, and she described the challenges they faced finding information about the officers who killed Oscar. These family members went on to found the Love Not Blood Campaign, which has provided an essential network of support for the ever-growing community of Californians who’ve lost loved ones to police violence, a community that has been at the forefront of a statewide movement against impunity and state violence.

Meeting with the families, and learning more about their work and their goals, served as a reminder of the first lesson I learned about human rights when I came to work at HRDAG. Ours is a movement of and for survivors.

Photo by Tarak Shah, CC BY SA 4.0

II.

Accompaniment is a practice that emerged in response to violence against human rights defenders in conflict zones. Organizations like Peace Brigades International developed a model where international volunteers would physically accompany threatened activists and communities. The premise was simple but powerful: the presence of international observers raises the stakes for potential attackers.

Several of my colleagues, partners, and mentors in the field got involved in human rights work through accompaniment, and it continues to shape their (and through them, my) work today. Last year at an event, Berkeley Copwatch co-founder Andrea Prichett described her experience doing accompaniment in the West Bank. When someone in the audience asked what accompaniment was, she explained, “it’s what they call cop watching in Palestine”. The practice is central to HRDAG’s own history – our Director of Research Patrick Ball’s work doing accompaniment is what took him to El Salvador. His work there building databases of testimony from conflict survivors marked the start of what became HRDAG.

Data scientists from the Mexican human rights organization DataCívica work with families of the disappeared who are searching for the remains of their loved ones, incorporating diverse types of data into machine learning models used to predict likely locations of fosas clandestinas. The work helps directly with the search effort, helping self-organized brigades prioritize areas to search. It also shifts the burden of holding or asserting information about perpetrators and grave locations, echoing the goals of the accompaniment model.

At one point DataCívica considered working with local authorities to get access to their data in order to expand and improve their models, but decided against it in order to remain accountable to the families they were serving. Understanding who they were accountable to shaped the goals of their work, how they defined impact.

Violence and trauma are isolating, and seeing patterns in data can help people understand they are not alone. As part of Beneath the Surface, trina reynolds-tyler and Maira Khwaja organized community meetings in Chicago to share our ongoing work surfacing complaints against police related to gender-based violence. In these meetings, people responded to the patterns that were presented by sharing stories of their own experiences, sharing resources, and making commitments to support each other.

Data science is a tool that can empower the people most impacted, or it can be something that further marginalizes them.

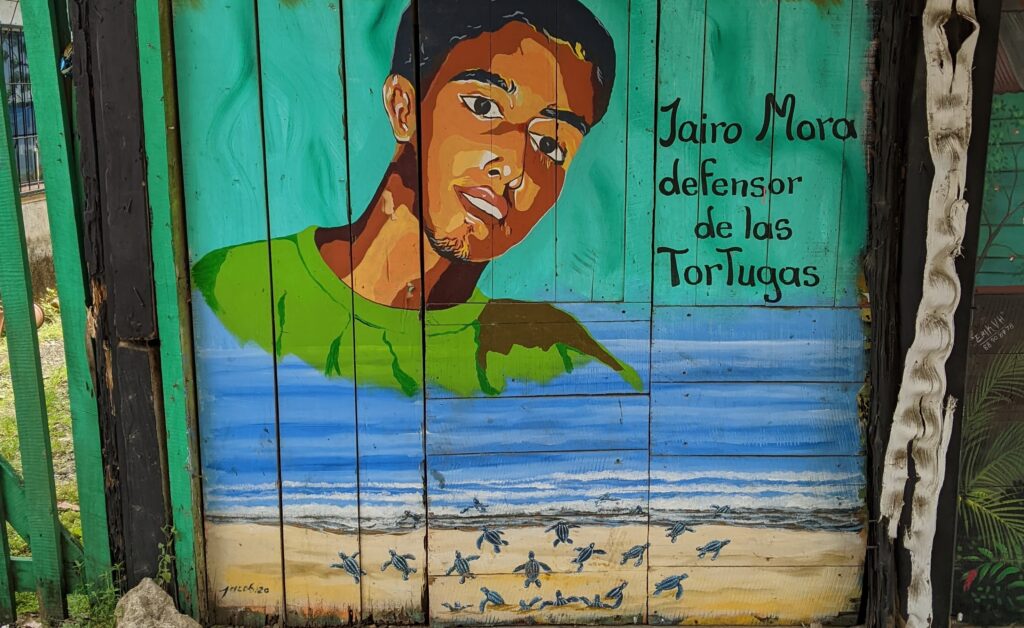

Photo by Tarak Shah, CC BY SA 4.0

III.

Methodological rigor is at the core of our commitments to survivors and the human rights movement. Scientifically defensible evidence and analysis can validate survivors’ claims and counter bad faith attacks (or grotesque lies).

Patrick put it this way: “Human rights stories tell about the worst events that anyone can experience. Taking responsibility for human rights information means assuming an obligation to the witness, to the families, and to the victim. We are morally obligated to do the best work that’s technically possible, so that the victim’s story is heard and believed.”

The tools and methods that have become central to our work reflect a commitment to empower survivors and the broader movement that centers them. That work begins with testimony, which must be translated into data for quantitative analyses. We’ve spent the last few decades studying and practicing the art and science of coding, understanding the ways that process has been used to gaslight and discredit (the schema is a world-view), using inter-rater reliability to help ensure the structured data we end up with is suitable for statistical analysis.

The data we work with results from decentralized and community-driven data collection, or includes counter-surveillance data such as FOIA or abandoned state documents. Doing analysis on these types of data requires extensive data cleaning and standardization to account for data entry variations, OCR noise, or physical degradation of paper documents, and we obsess over keeping those processing steps transparent and replicable in order to stand up to scrutiny.

Data is collective memory, and all of the ways we remember are data.

Those most vulnerable to state violence are already marginalized and undercounted, their experiences ignored or minimized in official sources. To avoid perpetuating these harms in our analyses, we have to find ways to incorporate unofficial data sources and all of the ways we remember, to produce reliable estimates with clearly defined uncertainty bounds from incomplete and patched together lists. Tools like multiple imputation and multiple systems estimation are perfectly suited to these problems.

Photo by Tarak Shah, CC BY SA 4.0

IV.

Reclamation isn’t just about the language we use to describe the past; it can happen in physical spaces.

The Chicago Torture Justice Center was established as part of the reparations program for survivors of torture under former Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge. Housed in a former mental health clinic that was shuttered due to budget cuts in the 2010s, the center exists to address the traumas of police violence and institutionalized racism. This mandate is expressed through a diverse and expansive program incorporating direct services, community organizing, and policy advocacy. These commitments all flow from a focus on healing and justice for survivors.

The neighborhoods around the Kilómetro Cero office in San Juan are named after bus stops along public bus routes that no longer run. A short walk from the office is La Goyco, a former public school that sat closed for years until community members occupied it in 2015. Today it is a vibrant community center, an oasis amidst a quickly gentrifying neighborhood, with a library, art studios, music classes, therapy, recycling services, a cafe, a kitchen, playgrounds, a garden.

Just up the road from the Ben Lomond Quaker Center is Big Basin Redwoods State Park, which was devastated by the 2020 CZU Lightning Complex fire. The landscape is still raw and scarred, nothing like the old growth forests just miles away, but there are signs of regeneration everywhere – baby trees just getting started, older trees regrowing their branches, bits of green sprouting from scorched trunks.

Over the past decade in California survivors and advocates have, through their efforts, created opportunities to apply data science in the fight to address persistent inequality and impunity. We owe them our best work, and we can only do our best work when we keep those who’ve been impacted at the center of it.

— TS

Structural Zero is a free monthly newsletter that helps explore what scientific and mathematical concepts teach us about the past and the present. Appropriate for scientists as well as anyone who is curious about how statistics can help us understand the world, Structural Zero is edited by Rainey Reitman and written by 5 data scientists who use their skills in support of human rights. Subscribe today to get our next installment. You can also follow us on Bluesky, Mastodon, LinkedIn, and Threads.

If you get value out of these articles, please support us by subscribing, telling your friends about the newsletter, and recommending Structural Zero to others.