Lessons at HRDAG: Making More Syrian Records Usable

Recently, I completed my time at Human Rights Data Analysis Group, where I had been a Visiting Data Science Student since October 2019. My time at HRDAG served as the working practicum component of my Master of Science in Data Science program at the University of San Francisco. During my practicum, I supported work on the Sri Lankan conflict and the Syrian conflict. I got familiar with the repository and data for the Syria work and asked about pain points in the analytical process for the project and in HRDAG’s work in general.

Recently, I completed my time at Human Rights Data Analysis Group, where I had been a Visiting Data Science Student since October 2019. My time at HRDAG served as the working practicum component of my Master of Science in Data Science program at the University of San Francisco. During my practicum, I supported work on the Sri Lankan conflict and the Syrian conflict. I got familiar with the repository and data for the Syria work and asked about pain points in the analytical process for the project and in HRDAG’s work in general.

One pain point brought up by one of my mentors, Dr. Megan Price, was missing information in one or more key fields of a record. The missing information results in not being able to include records in the record linkage (also known as matching, de-duplication, or entity resolution) process, because they are unidentifiable. An unidentifiable record cannot be included in the human rights violations used to extrapolate the number of uncounted human rights violations, and thus the total number of violations.

Some of the data sources HRDAG receives from its partners include unstructured text fields, such as a notes field, for additional information about a particular violation. If we could glean key missing information from those fields, we would be able to make some previously unidentifiable records identifiable, and thus useable in the analysis. One of the key fields necessary for identifying an individual in a record is governorate of death. (Governorate is a term for an administrative region of a country, around the level of a province or a state.) In the Syrian analysis, there were some records that were unidentifiable only because it was missing locational information in the governorate field. During HRDAG’s analysis of the total number of killings in the Syrian conflict from 2011 to 2015 for the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), translators working on translating some of the raw data from Arabic to English anecdotally found that some of the text fields not previously used for analysis contained governorate of death information.

The goal of my project at HRDAG was to devise a method to make some of those records identifiable, by gleaning governorate of death information from the previously unused text fields. This blogpost, and the accompanying technical post, details my process.

Background

Why is it so important to find additional governorate of death information? Having governorate information attached to records is a key piece to matching, also known as de-duplication or record linkage. Matching is the process through which we determine which records are about the same individual. HRDAG receives multiple documentations of human rights violations from partner organizations, and there are “overlaps” in the records of violations—where there may be multiple records from one or multiple sources about the same incident. An overlap does not need to be two records that are exact duplicates, and oftentimes is not: One record may list an individual’s age as 24, while another record might list it slightly differently at 25, while another record may not have the age field filled in at all, but may include other identifiable information. However, there is a minimum amount of information a record needs to have to be identifiable in the matching process. A record must contain at least three key pieces of information: A name, a date of death, and location of death—governorate of death in this case.

Multiple systems estimation (MSE), the statistical inference method through which HRDAG estimates the total number of human rights violations in a conflict, cannot be done until records are de-duplicated. MSE uses the previously mentioned “overlaps” in the recorded violations to estimate the number of unrecorded violations—victims who are not counted in any of the datasets used. Unidentifiable records cannot be matched and have to be estimated as part of the uncounted violations. This is why it is so important to find governorate information for records: Every additional record to which we can confidently assign a governorate of death, is an additional identifiable record that can be matched, and thus another record that can be used to estimate uncounted violations using MSE.

Motivation

From 2012 to 2016, at the request of United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), HRDAG worked to quantify the total number of documented killings in the Syrian conflict from 2011 to 2015, using datasets of documented killings from partner organizations. Different organizations may collect different information, and they may document and organize their data in different ways. Before MSE, raw data must be processed and standardized to allow for the different datasets to be analyzed together.

Part of this standardization process includes the transliteration of data from Arabic into English, and standardizing values from raw, unstructured text (an unlimited number of different possible values) to a limited, set number of categorical values. To transliterate and translate governorates and other fields, HRDAG used Google Translate (to automate large-scale translation) and worked with Arabic-speaking language consultants, whom we call oracles, whose translations and review of the automated translations served as a human check.

The process is iterative and resource intensive because of the many different forms of raw text that could be mapped to a standardized value. For instance, in the governorate field for the data source I was mainly working with, values would typically be descriptive text about circumstances of the killing, that may include mention of governorate(s) or other locational information—rather than a single governorate in Arabic that can be directly transliterated into English. To do the mapping, HRDAG created a dictionary mapping every unique raw Arabic text value to their English governorate, adding new mapping pairs to the dictionary as they worked on more sources. By the end of analysis, the dictionary mapped every unique raw Arabic text value in the governorate field to one of Syria’s 14 governorates, an identified location outside of Syria, or “Other.” This allows for all existing records with governorate information to be mapped to a governorate, but has limited efficacy on new sources and other fields (unless more translation was done).

During the translation process for governorates, oracles anecdotally found that some of the other fields in sources, not currently used for record linkage, contained governorate and location of death information. This opened for the possibility that there were some unidentifiable records, currently missing a governorate, that may list a governorate in another field. Previously, time and resources were not available to look into investigating this possibility. This is where I came in, and in this technical blogpost, I explain my approach, the technical details, and how we tested it.

Extensions and Conclusion

The approach I detail in the technical blogpost was meant to be exploratory and initial—using one of several possible available sources for Syria data, and without involving translation services by oracles, a valuable and limited resource. The work naturally extends to other data sources—both for other data sources within the Syria project, and potentially to other projects where there’s a compatible tabular data setup.

Additionally, the method itself requires more testing before it can be “productionized.” We have to verify that this method of imputing governorates produces a reliable “ground truth” as a base for downstream analysis. We need to make sure that we are confident that finding a matching English translation of a governorate in a location-related column, does in fact mean that the killing described by the record occurred in that location. Previously, the “ground truth” of translated governorate information was done using a combination of human oracles and Google Translate. In this process, we would want to verify the process with our Arabic language partners, and make sure that we apply our method conservatively to avoid misinformation. We tested the method using records with an existing governorate as the “real truth” to verify our imputed governorates, and found that 74% percent of records matched, suggesting we need to fine-tune our method more before implementation.

I also embarked on this project to see if we could glean more information out of the unused text fields with limited resources—including lacking a list of all the ways to write a Syrian governorate in Arabic (assuming different ways of writing or conjugating a word depending on context, as a secondary filter to catch any governorates missed in automated translation), without other text in the string. Having that could improve the efficacy of the process. Additionally, we are currently searching for governorates in a field about more granular location divisions—if we were to have neighborhoods or landmarks that map to a particular governorate and how they may appear in Arabic—that could also potentially add more identifiable records and also add a richness to our understanding of the data. Working with oracles would also help parse nuances in syntax missed by our automated translator—for instance, I have found translations such as “Aleppo Homs road”—is that Homs Road in the Aleppo governorate? Or Aleppo Road in the Homs governorate? Or is it a highway connecting both (which I had anecdotally found) and can be identifiable to neither location?

In sum, through a simple, automated translation approach, I was able to confirm the anecdotal theory that previously unused, unstructured fields in the data could be used to add governorate of death information to records that did not have it. Having gone through a first pass of the data using this method, we are also in a better position to engage our language partners in the next steps of improving and verifying the process. Finally, familiarizing myself with the text fields of the data put me in a better position for further exploring and extracting value from them in future projects.

For technical details about this approach and how we tested it, please read the full post here: String matching for governorate information in unstructured text, in our Tech Corner.

Acknowledgements

My time with HRDAG in 2019 and 2020 was supported by the Center for Applied Data Ethics.

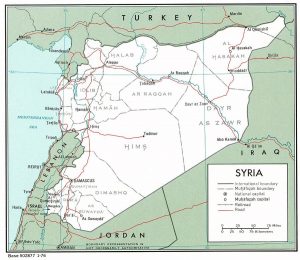

Image: Syria political governorate map with capitals of governorates from 1976, US government, Central Intelligence Agency – http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/middle_east_and_asia/syria_pol_1976.jpg